Sharpe: Why is it useful to demonstrate cropping systems and their outcomes to the public?

Reflections from students of an Agroecology course at North Carolina State University

This post is from Chloé Sharpe, who introduces herself as follows: I am a current junior at NC State University studying Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems, with minors in Extension Education and Nutrition. When I am not studying, I am often creating media for the University and College of Agriculture and Life Sciences or planning meetings and volunteering events at local farms for the Agroecology Club. I am from Four Oaks, NC, and spent lots of time in my youth helping my grandparents on their personal farm, where produce grown was used to feed my family and shared with neighbors. Seeing this seed-to-plate pipeline has made me develop a lifelong interest in and passion for agriculture.

Note: This series of student posts are only lightly edited to maintain the students’ voices.

As I design an agroecosystem for a small experimental plot at NC State University amongst my peers, memories flood of afternoons spent helping my grandparents on their small farm (or ‘large gardening’) operation back home. Those early experiences, hands caked in soil, gathering produce that fed not just my family but also our neighbors, formed the foundation of my passion for agriculture. Today, standing at the NC State Agroecology Farm, thinking about what other agroecosystem designs are needed to best demonstrate agroecological cropping systems, I found myself contemplating not just the methods but the message behind this agroecosystem I was designing.

My journey to becoming an agroecology student stems from my upbringing. In addition to growing up seeing the seed-to-plate process amongst my family, active years spent in FFA leadership roles nurtured my appreciation for agricultural education and community involvement. In addition, my recent internship with Extension in Johnston County allowed me to witness firsthand how suburban sprawl steadily consumed the very local farmland that defines what many others and I call home. As new residents move into rapidly suburbanizing areas, robust agricultural communication becomes essential in helping them understand their role within the local food system and appreciate the cultural and ecological value of agriculture in their communities. Effective communication can foster support for local producers, promote sustainable food purchasing decisions, and create advocates for farmland preservation. Farms that vanish, replaced by shopping centers and subdivisions, threaten rural livelihoods, diminish community food security, and disrupt ecosystem health by fragmenting habitats and reducing biodiversity. Thus, clearly conveying the importance of protecting agricultural land becomes pivotal in ensuring that both new and longtime community members recognize and actively support the interconnected value of local agriculture.

Furthermore, clear agricultural communication is vital in helping both farmers and the public understand the value of diverse, sustainable systems, not only for food production but for preserving the land itself. When growers are introduced to alternative models that still meet their productivity needs, they are more likely to engage with them. Demonstrating how ecological farming practices can align with economic goals helps bridge the gap between innovation and adoption. These communications are especially crucial in regions where farmland is disappearing, as they can inspire community support for preservation efforts and equip producers with knowledge to make informed transitions.

Facing these realities influenced me to promote the idea of a substitutive paradigm to my project group as our focus in the agroecosystem design project, one that strategically replaces harmful practices with sustainable alternatives. My goal was to create a conventional-esque cropping system, combining sweet potatoes and wheat with the strategic use of cover crops and reduced synthetic inputs. The approach aims to preserve or even enhance yield while dramatically reducing environmental harm and resource waste and presenting itself in a fashion similar enough to conventional systems that farmers who may be wary of converting their systems will feel comfortable. By grounding the design in familiar crop choices and field practices while subtly integrating regenerative techniques, we hope to make sustainability feel both achievable and practical, an incremental shift rather than a radical departure. In doing so, we focused on demonstrating that small, thoughtful changes can lead to meaningful environmental benefits without compromising productivity or economic viability.

But why should demonstrating such cropping systems matter to the public? Why should we, as agroecologists and agricultural communicators, commit to showcasing these designs?

First, visibility matters. When we openly demonstrate sustainable cropping systems, we are not just sharing knowledge; we're building trust. Many in our communities have grown distant from the food they consume, unaware of the labor, science, and ecological considerations that go into production. By actively demonstrating these sustainable agricultural practices, we bridge the disconnect between consumers and growers. Through transparency and education, the public can better appreciate what happens beneath the surface of their meals, understanding why sustainable choices matter, environmentally, economically, and socially.

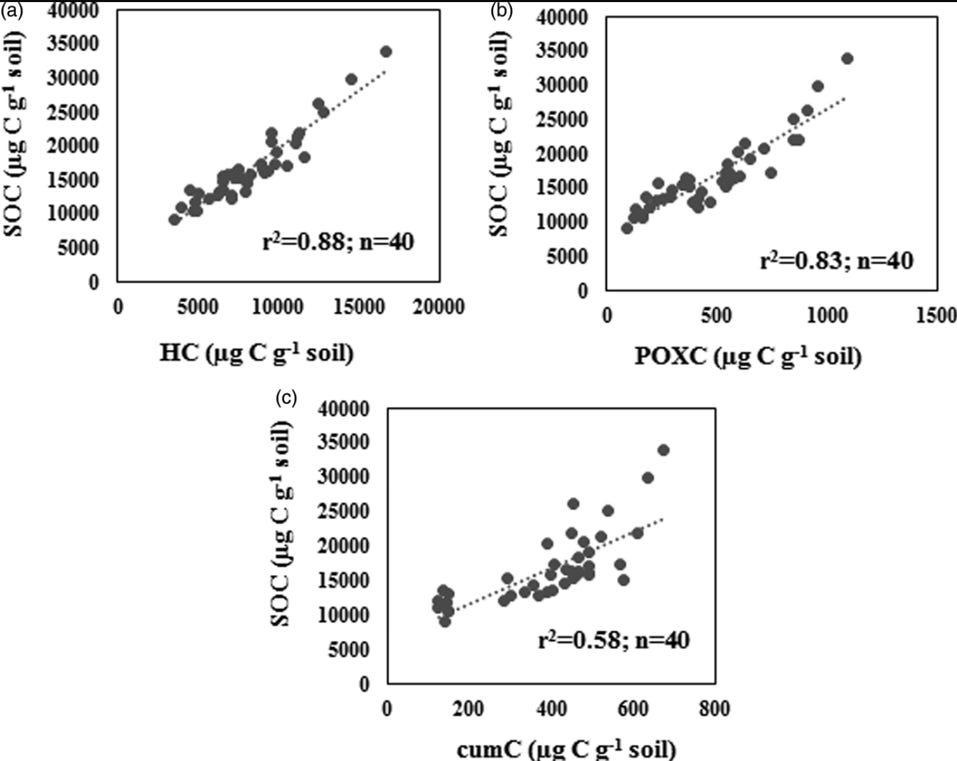

Moreover, public demonstrations have the power to influence policy and economic choices significantly. Policymakers, community leaders, and even corporate stakeholders often need tangible evidence that sustainable agriculture is not only environmentally beneficial but economically viable. While my project at NC State does not generate original data itself, it draws on a strong foundation of existing research that highlights the benefits of practices like cover cropping and substitutive inputs. Studies have shown that cover crops can improve soil structure, reduce erosion, suppress weeds, and even increase cash crop yields over time (Clark, 2007; Snapp et al., 2005). Likewise, substituting synthetic inputs with compost or manure has been linked to enhanced soil microbial activity and long-term fertility without sacrificing productivity (Bhowmik, et al., 2017). By basing our design on these established findings, we aim to communicate proven strategies in a format accessible to farmers and decision-makers alike, turning research into relatable practice and encouraging broader adoption across conventional systems.

“Figure 4. Interrelationship (linear regression) of total soil organic carbon (SOC) with (a) hydrolyzable C (HC), (b) permanganate oxidizable carbon (POXC) and (c) cumulative CO2–C evolved on day 90 measured as coefficient of determination (r2) across the five different organic management systems and two depths, 0–15 and 15–30 cm.” (Bhowmik, et al., 2017)

My agroecosystem specifically integrates cover cropping as a substitutive strategy to reduce chemical fertilizer dependency, hence minimizing fossil fuel use and improving overall ecological health. Cover crops like legumes fix nitrogen naturally, reducing synthetic fertilizer requirements. Meanwhile, their root systems combat erosion and enhance water retention, benefits easily seen and understood by anyone walking through the fields (Clark, 2007). Demonstrations clearly showcase these ecological gains, helping visitors visualize and appreciate sustainability in action.

Additionally, demonstrating cropping systems publicly plays an essential role in cultivating community engagement. Through my involvement in the Agroecology Club at NC State, organizing volunteer days at local farms, I've observed firsthand how direct participation can transform abstract ideas about sustainability into concrete experiences. Volunteers come away not only with an understanding but with a sense of ownership and personal responsibility toward their food system. This active engagement often translates into long-term support for local agriculture, reshaping consumer behavior to favor sustainable options.

However, the usefulness of public demonstrations extends beyond immediate environmental and economic benefits. They also fulfill a deeper, social function by affirming agriculture as a communal activity. Agriculture historically anchored communities, serving as a common point of interaction, cooperation, and shared responsibility. Reviving this communal essence through visible agroecosystems fosters unity, encourages dialogue about land-use decisions, and reignites collective investment in local environments.

As I reflect on designing my agroecosystem, the importance of demonstrating sustainable cropping systems grows clearer. It’s not merely about showing better ways to grow food but fostering broader conversations about sustainability, community resilience, and our collective future. Each demonstration site serves as a living classroom, a platform for education, and a catalyst for dialogue and action.

But as my journey continues, questions remain. Can visible demonstrations of sustainable cropping systems meaningfully shift public perceptions and behaviors on a broader scale? Can they truly impact policy or consumer habits long-term?

I turn now to you, dear readers, and invite your perspectives: Have you seen examples where public demonstrations of agroecosystems have significantly impacted your community's understanding and actions regarding sustainable agriculture? If so, how? Think about them and the impacts that have come or can come from them. Your experiences and insights are essential as we explore ways to deepen the connection between agriculture and the communities it nourishes.

References

Bhowmik, Arnab, et al. “Potential Carbon Sequestration and Nitrogen Cycling in Long-Term Organic Management Systems.” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, vol. 32. no. 6, Jan. 2017, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/renewable-agriculture-and-food-systems/article/potential-carbon-sequestration-and-nitrogen-cycling-in-longterm-organic-management-systems/0CA4C6AFC9CAD671C208BD04C51EA175

Clark, Andy, editor. Managing Cover Crops Profitably. 3rd ed., Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE), 2007, https://www.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Managing-Cover-Crops-Profitably.pdf

Snapp, S. S., et al. "Evaluating Cover Crops for Benefits, Costs and Performance Within Cropping System Niches." Agronomy Journal, vol. 97, no. 1, 2005, pp. 322–332, https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2134/agronj2005.0322a