Martineau: agroecology is hard as hell

Reflections from students of an Agroecology course at North Carolina State University

This post is by Eric Martineau, who introduces himself as follows: Eric Martineau is a graduating senior at n.c. state university. he will be receiving a b.s. degree in environmental sciences and plant biology and minors in science communication. he has always loved being outdoors and is deeply fascinated by the ecological interactions between humans and their food system.

Note: This series of student posts are only lightly edited to maintain the students’ voices.

“design a sustainable polyculture cropping system,” they said. “it will be fun,” they said.

as a senior in environmental science whose concentration is regenerative agriculture, i was assigned a final group project of turning a one-acre fallow piece of land into an agroecological cropping system for my advanced agroecology course. the cropping system can be designed under one of three paradigms: a high-intensity farm for maximum productivity, a sustainably blended substitutive system, or ecologically regenerative redesign.

immediately going into this assignment, i quickly learned how knowledge-intensive sustainability truly is. when designing an agroecosystem, you have to account for more than just which cover crops are symbiotic together or what’s the best method for controlling aphid populations without using pesticides. there are layers i never thought deeply about before taking this class: what tools and technology do you need to sow and reap your crops? once harvested, how will you turn your crops into something profitable? what markets will you sell to, and which support programs will encourage the stability of your cropping system?

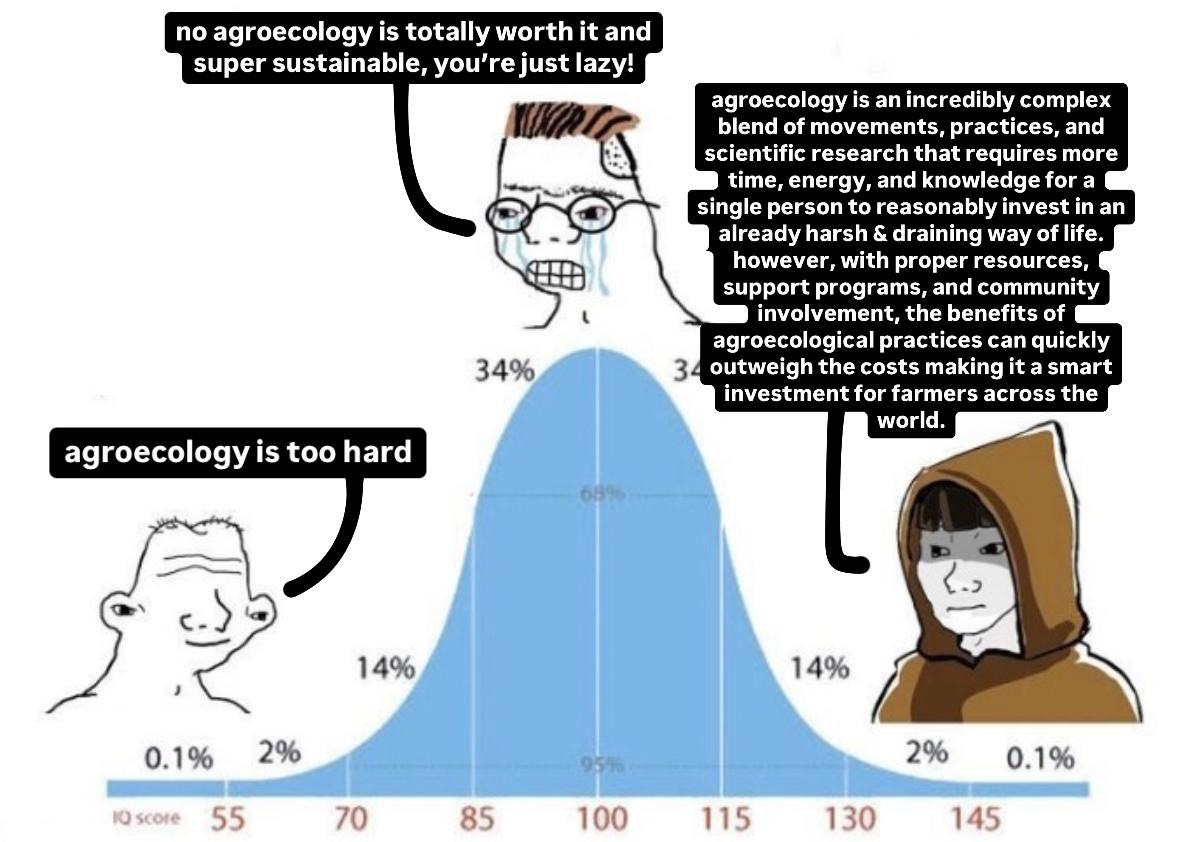

so why doesn’t everyone farm this way?

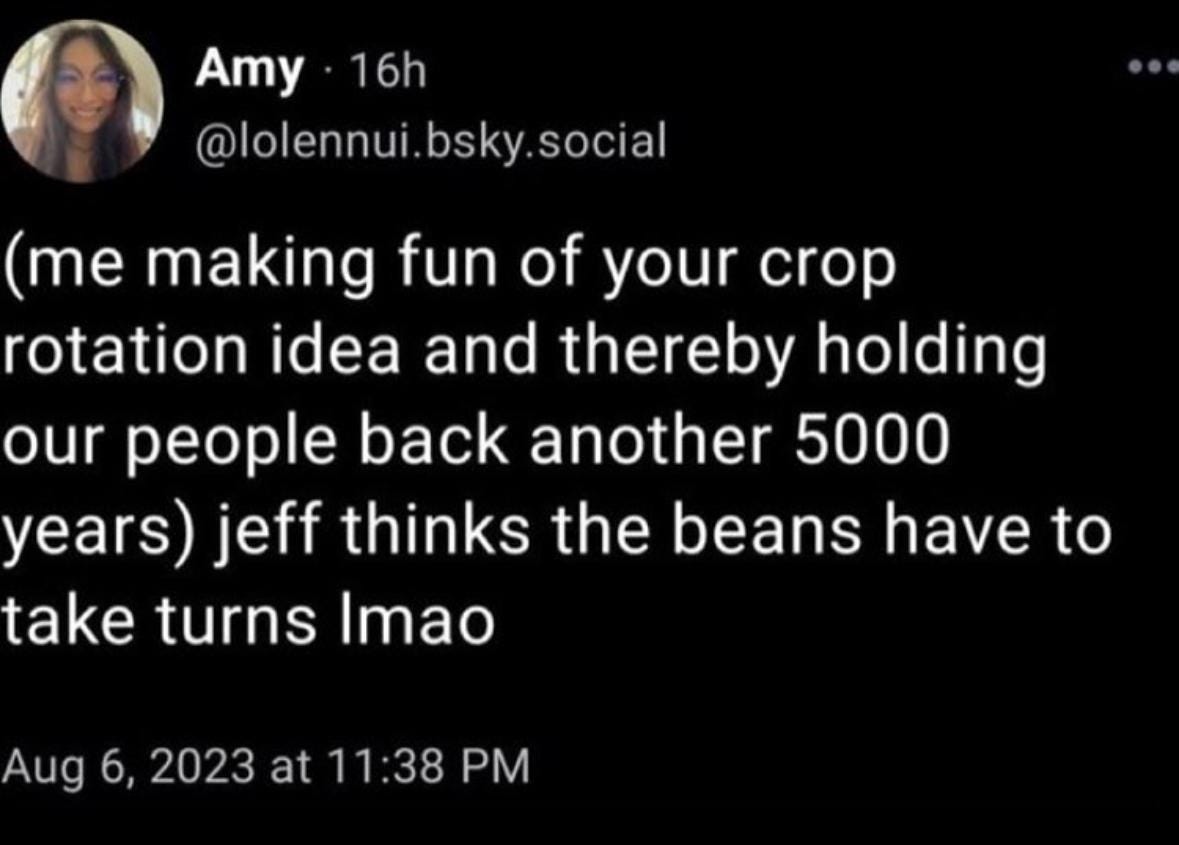

one of the first things beginners to agroecology ask themselves (myself included) is “why doesn’t everyone do this? its better for the planet, your pocketbook, and even your neighbor’s beekeeping side hustle!” but unfortunately for myself and anyone else who dives deeper into agroecology, the reality is a lot more complicated than that.

my perspective doing this project is one of low-stakes and low-stress. if my group and i design a complete failure of a cropping system, it won’t impact anything more than our grade, and as long as the rubric is met, we’ll still be able to pass.

on the other hand, if a farmer were to redesign their cropping system they have a lot more at risk. for farmers this is their livelihood, and for many of them it’s their history and their future. planting the wrong cropping system could mean the kind of financial ruin where you’re forced to sell your tractor before your tomatoes even fruit. that’s a lot of pressure for a lifestyle that is already notorious for early mornings, long days, and sleepless nights. so it’s no surprise that farmers rarely adopt new systems. if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

agroecology is incredibly knowledge-intensive; it takes years of experience to understand both the scientific research and traditional wisdom interwoven into sustainable farming movements. think about it this way: some people go to years of cosmetology school just to learn how to cut and color human hair.

now imagine how much time it would take for a farmer to learn about soil, machinery, crop science, climate, food markets, pest management, pollination, irrigation, and a million other factors at the same depth that hair stylists learn hair. it’s not possible. and this is not a diss against the beauticians of the world, but just an attempt at making the point that agricultural education may be the most complicated subject outside of medical school.

what i learned the easy way:

while putting together this cropping system for only an acre of land with a team of other people, I can't help but feel completely drained. i have never designed a farm before (outside of drawing old macdonald as a toddler) and there is a strong learning curve to this. all my respect to those who can understand the nuances of an agroecosystem like an horologist understanding gears.

each cropping system is completely unique from each other, and we need to remember that farmers are only experts on their own farms. asking a farmer to start growing asparagus instead of soy because it is more sustainable is the same as asking a cardiologist to become an anesthetist because the hospital is short on staff. it’s unreasonable without support programs that can provide the individual adapting with years of education and financial support as they transition!

within the tangled web that is our food system, there must be agents that can guide farmers through the adaptive cycle. governmental policy & support programs are a must for any chance at a resilient and sustainable food system that can provide adequate nutrition for consumers. not to state the obvious, but extension programs are one of the biggest life lines of american farmers and are the equivalent of a keystone species within the country’s agrifood system. american agriculture has become completely unrecognizable to farmers a century ago, and that is due in part to the economic support and education provided by extension offices and their partnerships with governmental agencies. farms can now make major changes in their cropping systems with more financial security as well as having access to the tools and education necessary for knowledge-intensive changes.

despite having unlimited access to the world's knowledge, i feel like i still don’t know enough to properly design an agroecosystem. i can’t imagine how a farmer, in the autumn of their life, is reasonably expected to become a regenerative agricultural warrior fighting for intercropping and integrated pest management without proper experiential training and formal learning. this is a lesson that can only truly be taught via failure, and luckily for me, it’s only an assignment for me: failure isn’t life ruining.

moral of the story is for all agroecologists to be a lot more considerate of conventional agriculture curmudgeons, who we may perceive as luddites but are actually just people trying to put food on the table for both themselves and everyone else in the world. that’s a heavy burden to bear, so the next time you want to roll your eyes at a farmer using roundup, remember: they’re not stubborn—they’re exhausted. and until we build a system that teaches, supports, and pays them to do better, we can’t expect miracles to happen.

I love this reflection! So many truths and a call for more grace from and for all of us trying to grow food in a good way.